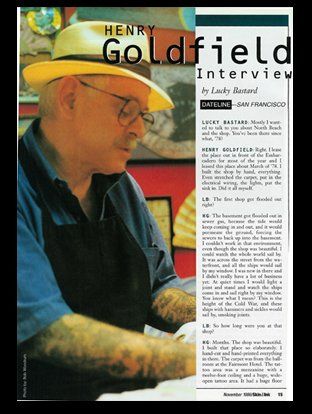

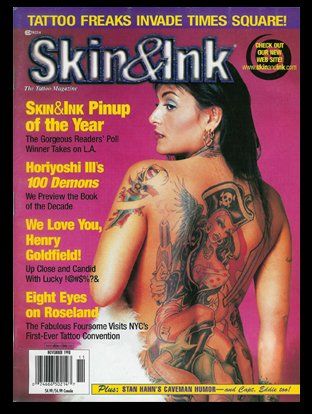

HENRY GOLDFIELD INTERVIEW

SAN FRANCISCO

When my cab dropped me off at the corner of Columbus the first thing I noticed was the well built young lady standing in front of one of the many nude bars that seem to be strategically placed about every forty feet as you walk down Broadway. The smell of cheap perfume and stale booze on the breath of the tourist definitely let me know I was in San Francisco’s “North Beach”. Although the main strip of Broadway is a lot more “user friendly” these days you can still feel the history in what was once a major hot spot for sailors on weekend liberty and other rough and tumble types. Yes, sadly the days of a good drunken brawl and getting a little more than a lap dance for your twenty bucks at the corner girlie bar have passed. But if a good fight with a liquored up swabie or a quick trip to the back room with a painted lady are not your style and you just happen to be on the hunt for a good tattoo and history lesson you will never forget then brother you have stepped to the right place.

Located at 404 Broadway Henry Goldfields tattoo studio is as real as it gets. A street shop is an understatement to describe this little slice of S.F. history. This is no appointment only “can I get you a fat free mocha while you wait for your consultation with the artist” bullshit tattoo “salon”. No way man, this is the real deal. Solid Tattoos with style deeply rooted in tradition is the order of the day with Mr. Goldfield and his crew.

The first time I met Henry I was about as much of a punk kid as anyone could be at seventeen. I was spending my time as a hang about at Bert Grimm’s shop no the infamous Long beach Pike. Doing my routine check out the old flash and bug Joe Vegas for another skull tattoo, in walked Henry with his family. I stayed only for a little while seeing that old friends were getting together and some teenage kid was probably not all that interesting to such a group of worldly people. Though it was a brief meeting it stuck with me for the rest of my tattoo career.

When next we met I was a little older and had some years of work under my belt. I knew that I had to get a tattoo from this icon of bay area tattooing. Walking in to get that piece that now adorns my right back arm was one of the most pivotal moments in not only my work but also in my personal life.

I arrived at the shop at four in the afternoon and was dropped of at my house by Henry himself promptly at one thirty the following morning. I learned more in that nine and a half hours than I had learned in my last year of working. I knew then that I had to get as many of these great stories as I could record. Since my second meeting with Henry I have spent many hours with the man and come to admire and respect him as not only a great technician in the field of tattoo, but have come to see him as a father figure, anyone who has ever asked me about Henry Goldfield I begin with the words “Henry, yea man he’s like my tattoo dad”.

Now what you are about to read is not the regular “what is your favorite piece to do” bullshit interview. This one kids is a history lesson that will be on the big tattoo test at the end of the semester. If you have any respect or love for the roots of this art form pay close attention to detail (because Henry does and he’s been here longer).

Lucky Bastard: Mostly I wanted to talk to you about North Beach and the shop. You’ve been there since what, ‘78?

Henry Goldfield: Right. I leased the place out in front of the Embarcadero for most of the year and I leased this place about March of ‘78. I built the shop by hand, everything. Even stretched the carpet, put in the electrical wiring, the lights, put the sink in. Did it all myself.

LB: The first shop got flooded out right?

HG: The basement got flooded out in sewer gas, because the tide would keep coming in and out, and it would permeate the ground, forcing the sewers to back up into the basement. I couldn’t work in that environment, even though the shop was beautiful. I could watch the whole world sail by. It was across the street from the waterfront, and all the ships would sail by my window. I was new in there and I didn’t really have a lot of business yet. At quiet times I would light a joint and stand and watch the ships come in and sail right by my window. You know what I mean? This is the height of the Cold War, and these ships with hammers and sickles would sail by, smoking joints.

LB: So how long were you at that shop?

HG: Months. The shop was beautiful. I built that place so elaborately. I hand-cut and hand-printed everything in there. The carpet was from the ballroom at the Fairmont Hotel. The tattoo area was a mezzanine with a twelve-foot ceiling and a huge, wide open tattoo area. It had a huge floor down front that was all carpeting, with globe lights hanging from the ceiling, brand new. I sunk a fortune into that place. It was a lot of work. And then I couldn’t keep it. I was there from March to November.

LB: So you pretty much lost that whole thing?

HG: All of it. Lost it all. I invested enormous sums of money in that and built it by hand. Hauled in huge amounts of lumber by myself, manhandled it all in there. Did it all by hand, measured and fitted it. Raised the floor in the back. Built walls, studded it, Sheetrocked it.

LB: So what was North Beach like back in ‘78 on Broadway when you moved up there?

HG: I’d never known North Beach. You have to remember what when I came here I didn’t have time to go out and party. I never really did any hanging around on Broadway. But that place, I painted the windows shut. Most of the windows were missing in the whole front of the shop. I taped the whole thing shut, boarded it over, gutted the place and started building by hand. At that point I didn’t even have a vehicle. So we’d go to the lumber yard, and I’d have this massive list of construction materials. I would hand-pick every damn board. I’d get mountains of this stuff. I was so into building the shop that I was thinking I would deal with the neighborhood later. But first I would shut it out. I remember walking out one day, and my wife was there to help. This woman I was married to, she says, “I think I just saw George C. Scott walk by.” Such bullshit. So, after we’d finish our day’s work and we go outside to lock up, there’s movie trucks all over the street, and they’re shooting a movie. Well, that might seem insignificant, but you have to remember I knew there were people in the street, but I hadn’t really paid attention to what was going on there. Now I’m building a shop, and suddenly, I realize that what’s going on in that street is good for business. I’d been down in the Embarcadero. I said, “Wait a minute here, did I really score or what?” So when I got open, I started working, and it was good for me. It was hard for a long time. I had no reputation, no nothing, when I got started.

LB: Who was here at that time? It was you and Lyle Tuttle? I know Pat Martynuik at Picture Machine was there.

HG: He was there in ‘76. Lyle was on Seventh Street, and Pat was on Geary. But then Lyle opened the shop the same time I did on Columbus. He was going to have two shops, and then this shop would be the one to replace that one. And he did it. But then, for one reason or another, he wasn’t really happy there, because there were a lot of people and all. I don’t know. But for some reason he would rather be down on Seventh Street, so he was down there for awhile. And he was really nice to me over the years. I remember him saying his dream was to have a restaurant, a tattoo restaurant. And he did it. When I got open here, I was there for some time, and then Sailor Moses came to work for me.

LB: He was the first guy that you ever had come in to help you?

HG: He was the first full-time guy. I had a kid by the name of Tommy Sylvester that came and I gave him a gig on Sundays. He could sit in for me on Sundays, but he would come around almost everyday. He was never full time. But when Moses came he was a down-home, straightforward, no bullshit kind of guy. And nothing was going to get in his way. And he spent two years there. Those were ass-kicking years, man.

LB: That was back when the Navy was still here. When Broadway was a pumpin’ place to be.

HG: The club scene ruled on Broadway.

LB: That was really good for business, the whole punk-rock thing.

HG: Yeah.

LB: You were right there, man.

HG: And then the Navy was there, and I had that sewed up. The kids from Treasure Island, they were sewed up.

LB: You tattooed all the damage-control guys and all that?

HG: Yeah, before that they were called polecats. I’d put like 25-color tattoos on them, and they couldn’t fucking believe it. They were hoping to get something better than red or green. They’d say, “How many colors?” and I’d say, “I’ll give you 25.” Wow, man! The emblems needed it. That’s what I had to do. When I first opened up that shop, the I.Q. of Naval personnel was right at about ten. The recruiters were having such a hard time getting personnel in the Navy that they were doing kids’ little entrance exams for them to meet their quotas. Everyone of them were drooling idiots. But I Loved them. They were great. They’d come in, look around and say, “I want to get this one, and this one, and this one, and this one. I’m gonna get four.” And the other guy would say, “Why are gonna do all that?” “Because I like them.” They’d do like four. And I think, Jesus Christ, man. They were only there for like three weeks and they’d get 24 hours to show up in San Diego for their second eight weeks of training. By that first three weeks they’d come out of there with five or six tattoos. Big ones!

LB: You definitely hooked those guys up with the good tattoos, all those Navy guys.

HG: The thing was, I grew up in the Navy. I could talk to them.

LB: So you had Moses there for awhile but you also had some other really good people working there.

HG: I can’t even begin to go down the line of people that I’ve been working with.

LB: I think the one whom everyone’s familiar with has got to be Greg Irons-the time that he was there.

HG: He was sweet man. We had a great time together. We would walk the street to get a cup of coffee to go. I never wanted to sit around in that coffee shop. He wanted to sit down and have a cup of coffee and relax and talk about tattooing. I was in no mood to do that whatsoever. If I’m gonna drink coffee, I’ll get it in a Styro and take it back to the shop and start tattooing customers. So we went up there to get the coffee to go and we’re walking back across the street. We’re carrying cups in our hands, and they’re hot, you know. And he says to me, “You know, Henry, these are the good old days.” And I knew exactly what he was talking about.

LB: Do you think that scene in the late ‘70s early ‘80s was what revolutionized and brought tattooing back to what it is now?

HG: It actually began before that. It started in the very early ‘70s. Suddenly it changed.

LB: Well, anyone that knows anything about tattooing in San Francisco knows that the main ones were Ed Hardy and Lyle Tuttle out there promoting it. And there was you and Pat Martynuik actually doing it.

HG: It was Pat. I was a rookie. Ed was tattooing. He was extremely prolific. Lyle was too but, at that point, he was doing a lot of promoting. Lyle is a great promoter.

LB: I mean, as far as street shop tattooing, Ed was doing his cool Japanese stuff, but as far as working-stiff tattoos, it was definitely coming out of your shop and Pat’s shop.

HG: You know, the funny thing is that I never saw it that way. In my head, it was coming out of Lyle’s shop and it was coming out of a lot of other shops, and I was the new kid on the block. So I didn’t see it that way. Not at all. There were tattoos coming on from all over the place. The Pacific Fleet was getting tattooed all the time. They would come back with stuff I couldn’t believe. Each time a ship would come in they’d have all these tattoos with words spelled wrong and lines crooked and everything. They were great tattoos-for like $6. And they’d say, “How much would you charge to fix this up?” And I started telling people, “I don’t do touch-ups anymore.” Other shops thought I was stupid, because that’s where the money was. But I found out that, if I told them I didn’t do touch-ups, they’d get a new one. And that’s where the money was. Because, if they paid six bucks for a tattoo, they’d only want to pay $2 to have it fixed up.

LB: I remember somebody saying that you’re not big on cover-ups and fixing other people’s tattoos.

HG: The shops around the Bay Area-they’re all my friends now-they would say things like that. “It’s stupid you don’t do cover-ups.” I’d say, “You don’t understand. I can’t do them. If I did, I wouldn’t survive.”

LB: Because you were on Broadway, you were in the light more. Pat’s shop was way out in Richmond. He was doing work. He was always doing work. But you were right on Broadway. You can’t miss Goldfield’s. When you’re going to a girlie bar or whatever, you always see it.

HG: But I didn’t know that. I thought, I hope somebody knows this place. Because people used to come in and say, “What is this place? Who are you?” The hotel was upstairs. You know how many dead people I’ve seen fall out of that hotel, full of holes? Over and over again, a common occurrence. They’ve changed over the years. But that place was brutal.

LB: It used to be a rough neighborhood. Was it really a tourist attraction?

HG: It was. You’ve got to remember that it was the Barbary Coast. When I opened up, all this weird shit was going on. People were getting stabbed and shot out front. And through all of that, there would be all these tourists from Fisherman’s Wharf with their kids eating ice-cream cones, and they had cameras and everything. And Japanese people would come in and take pictures. It’s not so much like that anymore. You know what, Lucky? One night years ago, I went home and turned on the tube. I sat down to cool my heel a little bit, and there was a documentary in black and white about North Beach and Broadway in the late ‘60s. I saw George Martin, the doorman, who is now older and bald, when he was younger and he had a crew cut. He was barking, getting people in the door for a live love act and all that. And Broadway was solid white hats. It was in the middle of the Vietnam war. The streets were packed. The narrator on the documentary said that between Fisherman’s Wharf and up Columbus and on to Broadway there were at least a 100,000 tourists, including servicemen, on any given night of the week.

LB: There’s just nothing like that anymore anywhere. It’s just not like that.

HG: This guy came into the shop, a young man, he came to San Francisco-this was about two years ago-and he was wanting to go to where the scene was happening. And I said, “What scene? The party’s over, man.” And he said, “I’ve been going all around the world. I’ve been going to all these places where it happened, and everyone says, ‘You should’ve been here five years ago. The party’s over.’” I said, “You’ve got to wait for the party to happen again.”

LB: Do you see that coming in North Beach? Do you think it’s gonna happen again? Cycle back and get to be that big?

HG: Yeah. It’s happening right now but in a different manner. It’s very calm. I’m very happy. I don’t have to enforce the shop with a baseball bat anymore. They come in the shop, they say hello. I don’t have to fight with anybody. Everybody’s polite and gentle. And what happened was that all that crowd either drugged themselves to death, or they’re out of work and they can’t afford to go to Broadway. I have to say this, I’m not that smart. I would sit there and go on endlessly with some tattoo I was working on and people would tell me that I was stupid, that 20 minutes on a tattoo was about the limit. You’ve got a guy working in a chair and he puts in more than 20 minutes, he’d better start wrapping it up or look for another job, because time is money here. And I’m sitting here working on these tattoos for five hours at a whack. And I used to try to justify that by saying that it was social security, if I did that. I’d probably get their kids, and I see that now. A lot of those people that I took my time tattooing years ago, I’m now getting their kids. That’s good business.

LB: So tell me a little bit about Amund Dietzel. You’ve touched on the subject before, but I’d like to hear the whole story about your relationship with him.

HG: In 1955, I was growing up in St. Paul, Minnesota. I was a skinny little guy, about 110 pounds. I was the guy that wore his pants down around his ass and rolled his cigarettes in his sleeve and all that. I was into Bill Haley and Fats Domino and Elvis Presley and all that. I wanted to be a tattooer, man. And I found a place where I could get a couple tattoos. I found out about this guy that was actually a tattooer. He was an old carny and he was tattooing in his basement outside St. Paul. He was a cabinet-maker and an alcoholic, and he was completely tattooed, completely covered, from his neck to his feet. I talked my friend into going out and I got a tattoo. We ended up in a car chase. The police chased us, and we got away. We wrecked the car and left it in the road. That was pretty weird. But anyhow, I did get tattooed by this man a couple of times. And then I heard that there was a tattooer in Milwaukee, which was about 400 miles away. And, sight unseen, I ran away from home. I left home in the middle of winter with three dimes. I borrowed 30 cents from my friend Jimmy and with the clothes on my back, half a pack of Lucky Strikes and three dimes at about 5 o’clock in the evening, I started hitchhiking to Milwaukee. I didn’t plan anything, I just suddenly did it. I ran away. I hitchhiked through a blizzard. I made it 15 miles to the Wisconsin border. It cost me 10 cents with a student card to get to the edge of town on the bus. So that was the first dime. But the thing is, while I was waiting at the transfer point for the bus downtown, there was a penny gumball machine, and I broke the dime in the store and I bought two gumballs. That left me with 18 cents. I made it to the edge of town and I started hitchhiking. It took me three rides to get to the border, the Wisconsin border 15 miles away. This is in the early evening. It was just on the other side of the bridge. It was a long hill about 1/4 mile long with nothing in between. It was out in the country. And I’m hitchhiking, backing up that hill. And I kept hearing this trunk going beep beep. And I looked up and I saw the cab sticking out of the truck stop up there and I thought, Is he beeping at me? Then I ran and got in the truck, and the guy says, “Man, I thought you were hitching a ride. How come you didn’t come?” And I said, “I didn’t know you were beeping at me.” And he said, “Where are you going?” And I said, “Milwaukee.” And he nodded. So we started driving and I said, “Where you going?” and he said, “Milwaukee.” And that was a night to remember, in a 1950 semi, and he’s working two shift levers, steering with stomach as we go. And there weren’t no goddamn interstates as we went. It was two-lane blacktop, and snowflakes coming down at that moment. I had a pair of Levis on, a pair of engineer boots and a bomber jacket with a fur collar and a scarf. And that was it. And we started going into a big Mid-western blizzard. Driving blind. It was an amazing odyssey. We drove all night and into the next morning. From where he picked me up, we’d gone about 70 miles down the road. And he says, “We’ve got to get a bite to eat,” and I say I’m not hungry, but he insists and he takes me in and buys me a steak, coffee, everything. And when we went to leave he said, “You forgot your cigarettes.” I had run out, but he bought some for me. We went through that blizzard, and it was brutal. We saw cars turn over right in front of us. Come sliding down the road. We made it all the way through. It was quite a trip. When we got there, he gave me directions on how to find a friend of mine that lived there. He gave me a half a buck for bus fare, and I went and found my friend who drove me down to Amund Dietzel’s, and Dietzel wouldn’t tattoo me without an I.D.. So we went over to a friend of his that worked in a parking lot and bought his I.D. for about $2, and we went back and Dietzel tattooed a bird on my shoulder. A couple of days later I hitchhiked back to Minnesota with my tattoo, my bird. And, when I got in town, I got arrested for being a runaway, and they put me in jail. I spent the night. My mother finally got me out. And I started making a few trips to Milwaukee. Then, after my junior year of high school, I talked her into letting me live in Milwaukee for the summer. I went down there and got a bunch more tattoos. I saw this sailor girl tattoo on the wall and I fell so in love with it, I just had to have it. but I figured I couldn’t get it because I wasn’t in the Navy. And I just loved that tattoo so much, I talked my mother into letting me drop out of high school and join the Navy. So she signed me up. And they sent me down to Great Lakes for training, and I went over there and got that damn tattoo.

LB: Where did Sailor Moses fit in all this?

HG: The thing was, nobody ever talked to people when you got tattooed. The point was, you don’t fucking talk to them. Put the work on, get ‘em out. You pick ‘em, we stick ‘em. If it ain’t on the wall, we don’t have it. Don’t talk to me. Forget it. I don’t even want to know your name, right? So Moses and I would sit around when there were no customers--we’d sit around and practice ways to talk to people. Words to say to really lighten them up and things like that. There were customers that would come in really being nasty and everything. They’d come in really out of control, disrespectful, nasty. So Moses would scream at them to shut their god-damn mouths and behave! He’d get them all humble and everything, but then they wouldn’t want to get tattooed by him, because he’d just screamed at them. So then I would step up and say, “Hi, how are you?” and they’d think, Finally, a sane person. Someone we can talk to. So I’d do the tattoo. And sometimes I would be the bad guy for the day, if I felt like it, and this would go back and forth. The problem was that Broadway was really energetic, and being the security force and the tattooer, right, I would get beat up trying to be the security force. I ended up in the hospital a number of times just trying to keep things straight in the shop, which is why I appreciate how things are now. People aren’t as wild as they used to be. It’s a quieter and gentler time. I heard that from some guy that used to be president.

LB: So you joined the Navy and you got tattooed again by Dietzel.

HG: I got tattooed as a runaway by Dietzel and I got tattooed by him when I was just living there working for a landscape company as a young kid. Then I got tattooed by Dietzel as a boot sailor. Then I went on my way and didn’t see him anymore.

LB: That was the last time you saw him?

HG: Yeah. I wrote to him in early 1961, asking him about an apprenticeship. And he wrote me a nice letter saying he was working the shop with his brother, Tattoo Thomas. And then he went on to explain that in Chicago they had raised the age limit to 21 instead of 18, which ruled out a big piece of the United States Navy. And that took away Tattoo Thomas’s main customers, so he had to close out. And Dietzel said, “Why don’t you come up and work with me? And eventually he went blind. Lyle has a couple or three letters from him saying, “I put in some yellow you might like,” and that kind of thing. And one time the handwriting changed, and he said in there that his wife is writing for him because he’s blind at this point. But, right from the get go, when I saw it was Dietzel’s I knew it was beautiful. I’d never seen another tattoo shop that was as beautiful. He laid a lot of words on a young kid. Being young and silly and all that, I didn’t know, man. I was just trying to get tattooed. Hell, by the time I joined the Navy at 17, I had ten tattoos and I weighed 112 pounds. I told myself, “Someday I’m gonna be a tattooer.” He says, “Oh yeah.” Then I started asking him advice and all that, and he opened up a drawer while he was tattooing and showed me a tattoo machine he made and said, “This is the real thing.” And I couldn’t believe he was telling me this. And one time I came to get a tattoo, and he took me in the back room to show me his workshop, and I was awestruck. He showed me the flash he was working on. He had a Spanish bullfighter woman he was working on. When I was at boot camp, they would give you one 12-hour pass about eight weeks into the deal. And the point was to show you how to go ashore and come back without screwing up. And you were not allowed to drink alcoholic beverages, no matter what age you were. Nor were you to get tattooed. I rode the electric train from Great Lakes up to Milwaukee and I got off the train and I ran as fast as I could to beat all these sailors there, because they’d fill it up for the weekend. And I went up there and I got the sailor girl. It was $7 and 20 minutes. But, by a weird stroke of fate, I was able to get an extra 12-hour pass that nobody else got. And I did the same thing. I ran there, but when I arrived, there were three sailors in there who were almost as young as I. Dietzel was sitting there, he was ready for a big day. And he looked at them and , motioning over to me, said, “He’s got one on his dick.” He never talked like that. And, all of a sudden, they said, “Man, how was that?” And I was a big man to them all of the sudden. He really did that. He was great man. He was very precise about everything he did, his art. His arms were all old, blue tattoos that were extremely old and faded. I couldn’t see color in them anymore. I just think that’s the greatest look in the world. Those old blue arms.

LB: So you started tattooing when you were in the Navy?

HG: Yeah. After basic training they sent me to a ship out of Norfolk, Virginia. And, when I got there, I had to look around and get tattooed. In Norfolk it was illegal to tattoo. The law had been changed about six years before that. But across the bay it was legal. That’s where everybody got tattooed. I would go over there.

LB: Whose shop was there?

HG: Tex and Ann Peach. They tattooed me a number of times. And then Ann opened up a shop across the street. Business was food for them. She ran one, and Tex ran the other. They got a man working for them who was really good. But, being out of the Midwest and everything, suddenly I was thrust into that quadrant of the country, that upper East Coast, sailing with all those kids from Baltimore, New Jersey, New York and Philly. Wow, they had Italian guys and all that stuff, and that was way cool, and they had tattoos. And I said, “Where’d you get this? Where’d you get that?” I’m on this ship, a beautiful ship, and I’m standing on the highest point that personnel can be on. We’re over where the captain is and we’ve got binoculars, and I’m on watch with this kid from Massachusetts, and we’re both completely tattooed. We’re supposed to keep an eye out for enemy aircraft but we just sit up there and smoke cigarettes and talk about tattoos. And we’re out there over the ocean. It’s all beautiful. All these guys got tattoos from Brooklyn Blackie. And all the tattoo shops were still operating in Boston and New York. They got little stuff, little eagles with the ribbons and three stars over the head, all that shit. All these years later, I’m thinking about deck-force guys. The guys down in the holes get big tattoos, and the guys working on deck get pork chops. And I was thinking years later at the shop, how come I never done that? All I got was the little things. Three dollars and $6, a $10 cover-up by Tex Peace. I had a dollar-and-a-half tattoo that Shaky Jake did on State Street in Chicago.

LB: So how did you get tattoo equipment in the Navy on a ship?

HG: I bought some stuff from Milton Zeis and I set it up, but I didn’t have a power pack. So the thing was that I could get a rheostat. Back then, throughout Navy ships there were battle lanterns on every bulkhead. At every space there had to be at least three of these lanterns with a handle that you could slip off, if you needed. They were very bright and were powered with 6-volt, square, dry-cell batteries. They were auxiliary lighting, in case all the other lights on the ship went out. So, someone supplied me with case of these batteries, and I would run wires across the terminals. They were a volt and a half, so I would have wires crossed over all these batteries. And I had a brass cast machine, the Jonesy Squareback. I still have that frame. It’s a beautiful machine. I used to tattoo all these guys. I had jars of color and all that. I used to have photographs of some of that work but I lost them in the divorce. Yes, I tattooed quite a few people. I tattooed people in the torpedo shack and the electronics shack-anyplace I could set up. The problem was you can’t buy anything on the ship. There ain’t nothing for sale, and you’ve got to keep it tight. But I remember not having alcohol for great periods of time, so I would stir everything in bourbon. I would mix my colors in bourbon.

LB: So you tattooed in the Navy for awhile, then you got out.

HG: The United States had just plunged itself into the first recession since World War II. The economy had been rising up to this point, and suddenly, everything went flat. And I went out looking for a job. I was so damn dumb. I didn’t have experience to do anything. You couldn’t buy a job. Nobody was hiring in the first place. And so this guy got me a job with temporary labor at a window cleansing company. And I learned that and became really good at it. Then I moved to Colorado. Because I wasn’t a fall-down drunk and I was reliable, I did all right. I became a union man. I worked in that profession and tattooed here and there back in the ‘60s. And then I went into the window-cleaning business and I became a master and was doing buildings that nobody else could do, and designing riggings and things. Then came the time that I decided I was going to go to school. I was driving in my truck one day and I said to myself, “Face it Henry, you’re never going to get that degree.” So I turned around and drove into the neighborhood and to the local university. I got the forms, filled them out and just happened to be there at the right time. I filled out the papers and I got a scholarship. I just quit everything I did and went to school. I studied art. I got a degree in politics, but I studied art for four years and was taking political science courses. I had enough classes in either one so I just took the degree in political science. And after I got out of that, I ended up here in California, working for a window-cleaning company, two blocks from the shop.

LB: So you were doing the window-cleaning thing for a long time?

HG: Yeah, a long time. Tattooing here and there. But things weren’t very good in tattooing, not good at all. They were doing all right in Long Beach, and that was about it. A little bit on the West Coast. On the East Coast in the ‘50s and ‘60s, they were shutting tattooing down methodically across the country. They were a little bit less tolerant and they starting shutting things down. And then the Health Board in Southern California started coming down on the shops in San Diego. But instead of shutting them down, they decided that the shops should institute new methods of sterilization, autoclaves and stuff like that. Bottom line was, East Coast says, “You’re out of business.” West Coast says, “Here, do this and you can work.”

LB: So what do you think about the way things are right now, how big it’s gotten?

HG: I think it’s just great. Everybody worries, and they should worry. But I get people saying that the respect is not intact and things get cheaper by the dozen, and this and that, and I think that everything is working exactly right. Everything is in place. It’s just on a bigger scale. I don’t have to take files and hacksaws and make my tubes in the back room anymore. I can get stuff as fine as the medical profession can make that shit. The medical profession spent their years telling people that they could get cancer from tattoos. Meanwhile all their fucking patients are dying from cancer without tattoos, and tattooed people are walking around having a good time in life. Anyhow, I remember not that long ago I would have to lie to by needles from a needle company and get phony letterhead printed. And now, every time I get my mail, there’s five or six needles companies wanting my business, and they will make them to order as I want them. They send people personally out to ask me if I will buy their gloves. Now what does that mean? They smell the dollar, the buck. But I like that. I think it’s nice. I love supply companies. I like everything. I think that’s nice. Why should some of these painters like Rembrandt and whoever, why should they have to spend their lives fighting with people just to buy a damn brush?

LB: I don’t think anybody’s trying to keep it out if the hands of the professionals; they’re just trying to keep it out of the hands of the scratchers and the hacks.

HG: Well, you understand, Lucky, that there are no secrets on the face of the earth. There aren’t any secrets. The only thing is that you never put a loaded gun into a fool’s hands. That’s all. If you go up to someone and ask something, if it will benefit the world, they’ll tell you. If it will screw things up, they won’t. That’s all there is to it. The point is, the only thing that makes something a secret is if it’s a fool asking. And that’s the point. People always told me lots of stuff. That makes me feel good. That means they don’t think I’m a fucking fool. I’m no rocket scientist, but everyone’s been so nice and turned me onto so much stuff, and been so cool to me that I’ve been able to eat.